Sandeep Silas visits the Indonesian island and comes back with memories of tourist beaches, the music of the angklun and glimpses of India everywhere

How do you see a country of 17,000 islands? That when 6,000 of which are inhabited! So you go to the place you’ve heard most about and which promises a generous share of the sun and beach.

The word ‘Indonesia’ has an India connection — “Indos” means Indian and “nesos” means islands.

India here is every where and in everything — statues from the Ramayana at road intersections; people greeting you with “Namaste”, temples, folk performances of the Ramayana, wood craft, the confusion of shops coming right up the street, and the unevenness of order. The reason was not far to find.

Indian traders brought Indian culture and religion here in 1st Century A.D. In 7th Century A. D. the Buddhist kingdom of Srivijaya in South Sumatra was epitomised in the building of the Borobudur Buddhist sanctuary. In 13th Century A.D. East Java saw the emergence of the Hindu empire of Majapahit, which lasted two centuries, uniting Indonesia and parts of the Malay peninsula. The Indian Government is helping restore the Prambanan Temple near Yogyakarta. Islam came in the 16th Century, again with traders, and today is the dominant religion here. Interestingly, Marco Polo came to Java in 1292 A.D. but the Europeans did not come until the 16th Century, when the fragrance and flavour of spices could not hold them back anymore. The Portuguese, Dutch, Spanish, British, Japanese… all have been players in the archipelago till Soekarno proclaimed independence in 1945 A.D.

The road took me to Nusa Dua. Once inside the Italy-like tip of the Indonesian shoe, I learnt it is an insulated area for tourists, with little or no interaction with Indonesian people save what is dished out by the hotels. Past the Namastes, floral greetings and bamboo music it was left entirely to me to discover the Balinese way of life.

Nusa Dua Beach in Bali. Photo: Sandeep Silas

Nusa Dua Beach in Bali. Photo: Sandeep Silas

A break took me to Kuta Beach, which, along with Jembaran, is a favourite with tourists. Crowded, confused and scarred by the memory of the 2005 bomb blasts, the place still buzzes like a bee.

A while later I saw the most stunning examples of woodcraft. Most of them celebrate Jatayu’s sacrifice as it tried to protect Sita from being captured by Ravan. Ram and Sita, too, were captured in wood.

I selected a depiction of an Indonesian couple in the rice fields as a souvenir, having enough of the Ramayana in my home country. The batik here is irresistible, so be prepared to be divested of a few thousands of rupiahs if you enter a showroom. One thing I must record is the simplicity of the ordinary Indonesian. They appear so human and appear so starry-eyed as they feel that your situation in life is better. The very mention of ‘India’ generated a friendliness.

The beach was calm. Sea-washed! I sighted fresh algae that the waves had brought to the shore.

Click, click, click went the shutter, capturing the golden road to the sun on the water surface. It lasted about ten minutes, this heavenly bliss before normalcy returned and it was like any other day. The virgin rays falling on the beach, the trees, the beachside temple and on my face were all in my camera.

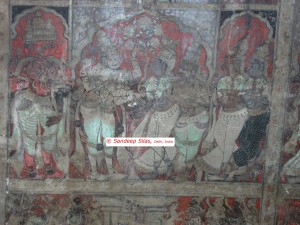

Next day was a day full of diplomatic nuances, debates and a draft declaration. The evening promised Ubud — rice fields and ethnic dance. I travelled almost an hour from Nusa Dua and reached a restaurant complex called Laka Leke, situated amidst the rice fields. Everybody sits here in spacious pavilions and witnesses the Kecak and fire dance. The venue is illuminated by flickering oil lamps. When the queen enters on her palanquin, bare-chested men raise their hands and bow their heads in welcome. Kecak is actually the Balinese version of the episode of Sita’s captivity. The men play the monkeys, crying ‘cak-cak-cak’ and circling Sita as they dance, the fire adding an element of mystery to the scene. Hanuman, the monkey god, comes to rescue Sita, gives her the ring of her husband Ram and consoles her. Now, the only difference in the Balinese Ramayana and that which we know in India is that there the story ends with “lived happily ever after”, while in the Indian version she had to go through the ritual of Agni Pariksha (fire ordeal).

Nurturing culture: Ramlila in Bali. Photo: Sandeep Silas

Nurturing culture: Ramlila in Bali. Photo: Sandeep Silas

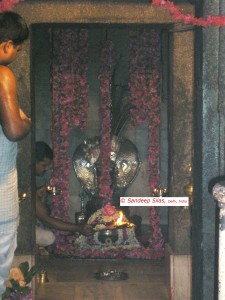

The Taman Ayun Jagatnatha, is dedicated to god Sang Hyang Vidi Wasa. The capital Denpasar has many community temples. There’s Pura temple in Mengwi sits on a tableland. All temples have a turtle and two dragons in stone signifying the foundation of the world.

The Balinese dress and dance during festivals — Galungan and Nyepi are the main ones. The harvest thanksgiving festival is Makepung and held from August 8 to 12 at Jembaran. The islands’ most famous sea temple is Tanah Lot, where rituals were conducted and offerings given to the guardian spirits of the sea.

The simplicity of Bali’s music appealed to me a lot. There is the angklun, an instrument made of slit bamboo, which is held in hand and shaken to release the musical notes.

I carried an angklun back home, and whenever I think of Bali I just go and give it a little shake.

Keywords: Indonesian island, Bali

(Published in The Hindu, May 27, 2012)

Note: 8 photographs added at the time of uploading.

Link: http://www.thehindu.com/features/metroplus/travel/by-myself-in-bali/article3462543.ece

![BEAUTIFUL THOUGHTS by [Silas, Sandeep]](https://images-eu.ssl-images-amazon.com/images/I/51T%2BzYeK4uL.jpg)